While I have used film for most of the time I have been a photographer, for the last decade, my work has primarily been with digital cameras. As a photojournalist often working in remote environments, digital technology has become the most practical way of getting images to publications. Even for domestic assignments, it is now the default for most photographers as clients balk at paying for film and processing, which used to be standard.

Taking on a personal project, though, is is a different story. You have the luxury of doing whatever you want, and at your own pace. For convenience, cost, and the enhanced ability to shoot in low light I took digital pictures everywhere I travelled for Seeing Buddha. But part of the process was to force myself into different ways of seeing.

Even more importantly, using a range of techniques would not only challenge and inspire me, the resulting photographs would reflect the variety of the many ways Buddhism is practiced and how those differences are reflected in the visual aesthetics of various cultures. In addition to using my Leica and Nikon digital cameras, I decided to use some film techniques exclusive to one location. For example, when I photographed along the Ganges in India where Buddhism began, I reverted to the 35mm black and white film that I started with when I was a teenager.

I also used black and white film for Angkor Wat, but of a larger type to make slightly hazy panoramic images using an $80 plastic Holga medium format camera. There are two photographs in the book which are double exposures created when I used the cameras improperly, resulting in beautiful accidents I could not have created on purpose.

To photograph exiled Tibetans in Dharamsala and Kathmandu, I used color negative film which was the dominant photographic medium of the late 20th century. This places those photographs in a certain time in history, acknowledging the political reality of this community. When I was in Sri Lanka, my first visit there, I loved the aesthetics of the native Sinhala script and wanted to somehow incorporate that into the images. After I returned, I created small one-of-a-kind Polaroid style black and white prints and took them to a Sri Lankan monk in San Jose, California and asked him to write onto the print itself. Those images are reproduced with his freehand script.

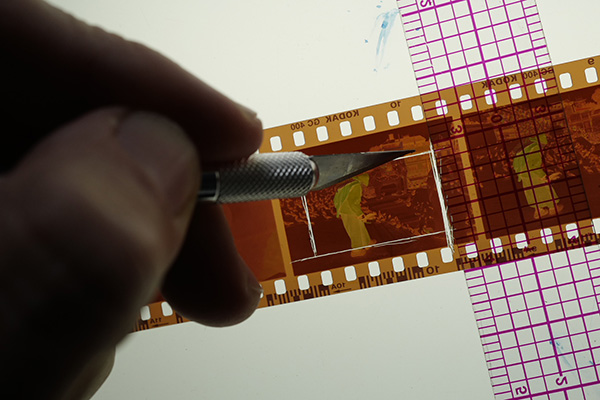

In Burma, I employed the most freeing technique of all. I used 35mm color negative in a Leica with a lens wider than usually use. I photographed scenes quickly and with a slow shutter speed, not concerned with edge-to-edge framing. I also underexposed the film and had it overdeveloped (push processing) to create a negative with the right density, but one that was grainier than usual. With the loosely-composed negative in hand, I took an exacto knife and scratched tighter frame lines into the image, committing to a permanent effect and composition.

This reminded me of the idea of the motion, intent and commitment found in Buddhist calligraphy. In addition, the combination of motion blur from the slow shutter speed, and the graininess from the crops and push processing give a much more impressionistic feel to the photographs than you’d have otherwise. To me this reflects the way most Burmese think of their religion, which is much more mystical and other-worldly than the way it is practiced in Japan, for example.

Could you acheive a similar look with digital manipulation? Probably, but by using film you’re committing to a certain type of picture in the moment you’re in the scene. You must be “present” literally and figuratively. That forces you into a mental, emotional and – with luck – spiritual headspace while you are interacting with the subject.

-David Butow

Comments are closed.